Free delivery on orders $350+

Free delivery on orders $350+

Connect With Us

Here’s something you probably didn’t know: an estimated one million Australians have swallowing difficulties, also known as dysphagia.

Despite advances in clinical care and treatment approaches, dysphagia continues to be a catalyst for another, just as serious health condition: malnutrition.

People who struggle to swallow food and fluid are at much greater risk of malnutrition than the general population, and, consequently, it’s the responsibility of healthcare workers and family members to help people with dysphagia avoid its potentially life-threatening impacts.

In this article, we’ll examine how dysphagia contributes to malnutrition, what the dysphagia-malnutrition relationship looks like in different settings, and how people with dysphagia can prevent and treat dysphagia-induced malnutrition.

Contents

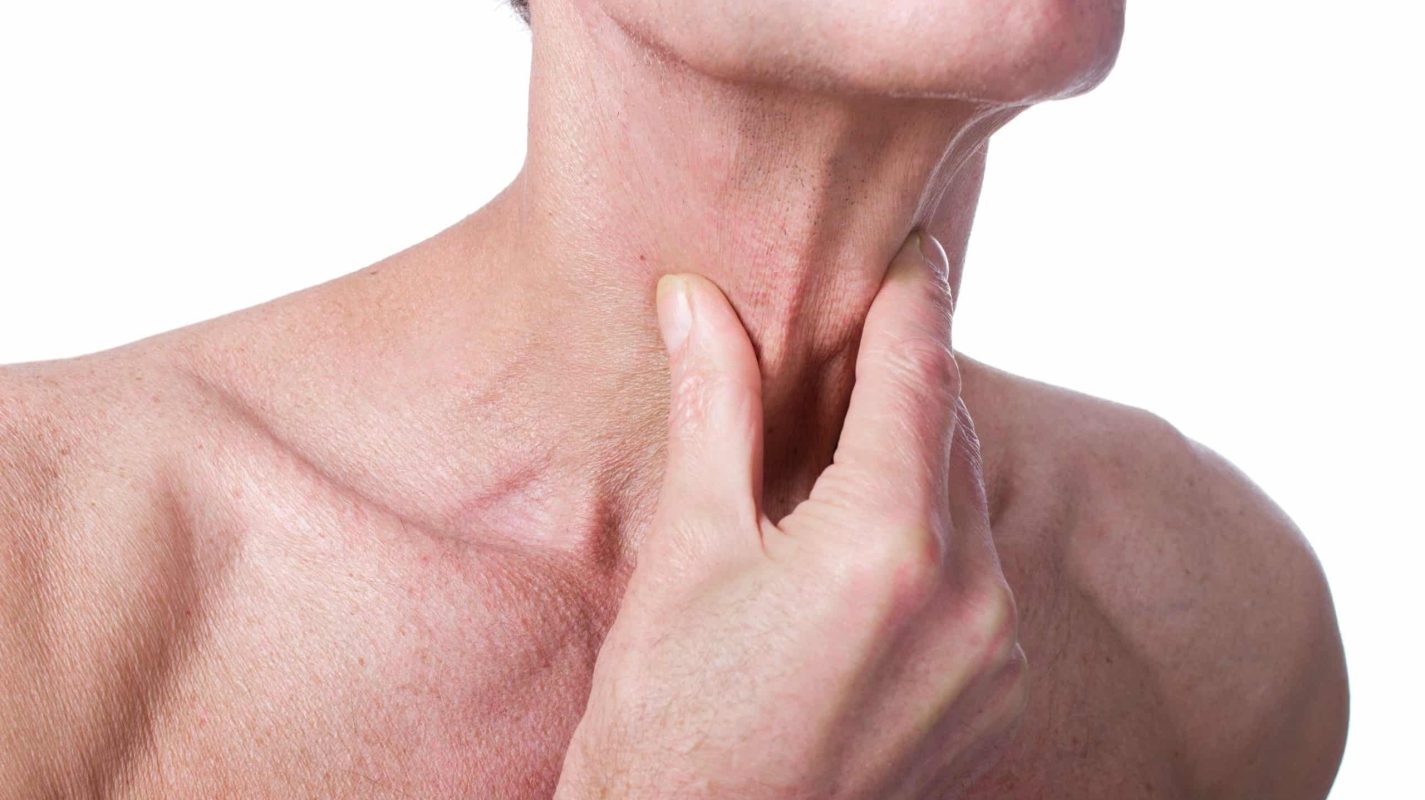

Dysphagia is the medical term for swallowing difficulties [1, 2]. People with dysphagia may have difficulty moving the food around their mouth or down their throat, and may cough, choke or even inhale food or fluid particles into their lungs as a result [1].

Dysphagia can be caused by many different medical conditions that affect the head and neck, including spinal injuries or surgery, cancer, stroke, neurological conditions like Parkinson’s disease, or even age-related muscle loss [3, 4, 5].

It’s particularly common in hospital patients and older people (those aged 65+ years), because both groups are often affected by one or more of the aforementioned conditions.

Malnutrition is an imbalance of energy, protein, vitamins and minerals that causes adverse effects on body shape, bodily function and clinical outcomes. Like dysphagia, malnutrition is incredibly widespread, affecting up to 40% of hospital patients and up to 50% of aged care residents [6, 7].

There are four types of malnutrition:

Malnutrition can be caused by a variety of factors, including poor diet, chronic disease, age, malabsorption, certain medical conditions, dementia and dysphagia.

The nutrients in food allow our bodies to repair damaged tissue, maintain muscle mass and keep our immune systems strong, so not absorbing enough of the macro- and micronutrients we need means we’re vulnerable to a range of different health conditions. These include:

Malnutrition is particularly dangerous for hospitalised and older people. Both groups often have pre-existing health conditions, and malnutrition can worsen the impacts of these, resulting in significantly higher risks of mortality.

To learn more about the effects of malnutrition, visit our Complete Guide to Malnutrition here.

Now we know exactly what dysphagia and malnutrition are, let’s take a look at how being unable to swallow properly can impact a person’s ability to get enough of the right nutrients.

Dysphagia can be either oropharyngeal (caused by problems with the mouth and throat) or oesophageal (caused by problems with the food pipe), but both types have the same end result: the inability to easily and safely consume certain types of food and liquids.

People who have dysphagia may eat more slowly, cough, gag or choke, struggle to keep food and liquid in their mouths, or even regurgitate food that they’ve tried to swallow. This, in turn, can make them less willing and less able to eat the right amount of nutrients, resulting in macronutrient undernutrition (which we’ll just call ‘malnutrition’ for simplicity’s sake).

Many different studies have demonstrated an independent association between dysphagia and malnutrition in older people, especially those in aged care homes [8, 9].

In a recent 2019 study, 30.1% of survey participants were at risk of dysphagia, with 50% at risk of malnutrition and 16% malnourished [9]. The study positively identified dysphagia as a risk factor for malnutrition.

A 2018 study of Dutch nursing home residents found that 20.2% of malnourished residents had dysphagia (although the study’s authors noted that the real number may have been underreported due to staff lacking knowledge about dysphagia) [8]. It, too, found that dysphagia was a risk factor for malnutrition.

Problematically, dysphagia-induced malnutrition in aged care can actually trigger a vicious cycle of frailty among affected residents. The physical effects of dysphagia result in less food consumed, which, in turn, leads to reduced functional capacity, which further impedes ability to eat, which leads to a loss of muscle and bone density, reducing functional capability and increasing the risk of other health conditions [14].

This spiral of ill health is very difficult to correct, and could have irreversible effects on your patient or loved one’s health.

Understanding how dysphagia can cause malnutrition is particularly important if you’re an aged care staff member or a relative of an aged care resident. If a loved one or someone under your care is showing signs of dysphagia or has been diagnosed with dysphagia, you should consult a speech pathologist or dietitian for dietary recommendations to minimise the risk of malnutrition.

Studies about the relationship between malnutrition and dysphagia in hospital settings also indicate that dysphagia can lead to malnutrition.

A study which examined the prevalence and risk of malnutrition on admission to New Zealand hospitals found that 26.9% of admissions were malnourished and 22% had dysphagia. The authors concluded that the risk of malnutrition corresponded with the risk of dysphagia [11].

A 2014 study of hospitalised elderly patients also determined that dysphagia and poor oral health could lead to malnutrition [12]. They attributed this relationship to dysphagic patients requiring specialised meal preparation, patients selecting ‘easy to swallow’ foods (leading to nutritional deficits), and slower eating habits leading to less overall food consumption [12].

Another study conducted in 2014 of Spanish inpatients indicated a risk of 30.8% and 15.4% for dysphagia and malnutrition respectively, with a definite correlation between dysphagia and increased risk of malnutrition [13].

While it’s certainly more common for older patients to be at greater risk of developing dysphagia, and therefore malnutrition, all at-risk hospital patients should be screened for both dysphagia and malnutrition, particularly if they are suffering head/neck injuries, have cancer, or have a neurological condition.

There are two phases of impact minimisation for dysphagia-induced malnutrition: prevention and treatment/management.

Prevention means stopping dysphagia-induced malnutrition before it starts. Typically, this requires staff and relatives to be aware of symptoms and to be proactive with screening tests.

As we now know, dysphagia and malnutrition are both very common conditions, especially in aged care and hospital settings, which means staff members need to be aware of the signs and symptoms of both conditions. If you’re a relative of someone who has recently entered either setting, or you’d just like to brush up on your knowledge, you can read about the basics of dysphagia here and the basics of malnutrition here.

Unfortunately, practical considerations prevent every facility from having the necessary resources for staff education or close patient monitoring, which means a more systematic approach needs to be taken. This is where screening tools can be exceptionally helpful for identifying at-risk patients and residents, who can then be referred to the appropriate specialists.

Many different studies have recommended that both dysphagia and malnutrition screening be introduced as a standard practice in hospital and aged care [15].

Most bedside screening tools are short, simple yes/no questionnaires that assign answers a numerical value; if the total score is above a given amount, the patient should be referred to a specialist for assessment.

Some common dysphagia screening tools include:

Other dysphagia tests, like videofluoroscopy swallowing studies and fibre-optic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing, are impractical for screening because they require skilled personnel and specialised equipment [17].

Well-validated nutritional risk screening tools include:

If a screening tool determines a referred patient or resident is or is at risk of being malnourished or dysphagic, a specialist like a speech pathologist will recommend a treatment or management plan.

The speech pathologist may work with other specialists, like dietitians, to develop intervention strategies to prevent malnutrition [14]. These can include [14]:

Most of these intervention strategies will be implemented by trained professionals, but you might find that your loved one or the person you’re caring for needs your assistance with preparing texture-modified foods and fluids. This will often involve adding thickening powder to drinks, or mincing and pureeing food.

To learn more about texture-modified diets, check out our Complete Guide to Texture-Modified Diets.

Dysphagia and malnutrition are, unfortunately, health conditions that go hand-in-hand. Difficulty swallowing can lead to difficulty eating, resulting in a vicious spiral of ill health.

The best way to combat dysphagia-induced malnutrition is through standardised screening tests, which can easily be administered by nurses, aged care workers and even family members. If a screening tool indicates your loved one or patient is at risk of either dysphagia or malnutrition, contact a general practitioner for a referral to a specialist like a speech pathologist.

Remember: prevention is the best type of treatment. Familiarise yourself with the symptoms, start regularly using screening tools, and keep the people you care about safe and healthy.

Medical information on FlavourCreations.com.au is merely information and is not the advice of a medical practitioner. This information is general advice and was accurate at the time of publication. For more information about nutrition and your individual needs, see your GP or an Accredited Practising Dietitian.

Dr Rebecca Nund

BSpPath (Hons), GCHEd, PhD CPSP

Dr Rebecca Nund does not work for or own shares in Flavour Creations, has received no funding or financial gain from reviewing this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

[1] Triggs, J. & Pandolfino, J. (2019) Recent advances in dysphagia management. F1000 Research. 8. DOI: 10.12688/f1000research.18900.1

[2] Rommel, N. & Hamdy, S. (2015) Oropharyngeal dysphagia: manifestations and diagnosis. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 13(1), 49–59. DOI: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.199

[3] Suttrup, I., & Warnecke, T. (2015) Dysphagia in Parkinson’s Disease. Dysphagia. 31(1), 24–32. DOI: 10.1007/s00455-015-9671-9

[4] Joaquim, A. F., Murar, J., Savage, J. W. & Patel, A. A. (2014) Dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a systematic review of potential preventative measures. The Spine Journal. 14(9), 2246–2260. DOI: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.03.030

[5] King, S. N., Dunlap, N. E., Tennant, P. A., & Pitts, T. (2016). Pathophysiology of Radiation-Induced Dysphagia in Head and Neck Cancer. Dysphagia, 31(3), 339–351. doi:10.1007/s00455-016-9710-1

[6] Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (2018, June) Hospital-Acquired Complication: Malnutrition. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/SAQ7730_HAC_Malnutrition_LongV2.pdf

[7] Dietitians Association of Australia (2019, March) Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. Dietitians Association of Australia. https://dietitiansaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/DAA_Royal-Commission-Aged-Care_Mar-2019_Final.pdf

[8] Huppertz, V. A. L., Halfens, R. J. G., van Helvoort, A., de Groot, L. C. P. G. M., Baijens, L. W. J. & Schols, J. M. G. A. (2018) Association Between Oropharyngeal Dysphagia and Malnutrition in Dutch Nursing Home Residents: Results of the National Prevalence Measurement of Quality of Care. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. DOI: 10.1007/s12603-018-1103-8

[9] Tagliaferri, S., Lauretani, F., Pelá, G., Meschi, T. & Maggio, M. (2019) The risk of dysphagia is associated with malnutrition and poor functional outcomes in a large population of outpatient older individuals. Clinical Nutrition. DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.11.022

[10] Namasivayam, A. M., & Steele, C. M. (2015) Malnutrition and Dysphagia in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review. Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics. 34(1), 1–21. DOI: 10.1080/21551197.2014.1002656

[11] Chatindiara, I., Allen, J., Popman, A., Patel, D., Richter, M., Kruger, M. & Wham, C. (2018) Dysphagia risk, low muscle strength and poor cognition predict malnutrition risk in older adults at hospital admission. BMC Geriatrics. 18(78). DOI: 10.1186/s12877-018-0771-x

[12] Poisson, P., Laffond, T., Campos, S., Dupuis, V., & Bourdel-Marchasson, I. (2014) Relationships between oral health, dysphagia and undernutrition in hospitalised elderly patients. Gerodontology. 33(2), 161–168. DOI: 10.1111/ger.12123

[13] Galán Sánchez-Heredero, M. J., Santander Vaquero, C., Cortázar Sáez, M., de la Morena López, F., Susi García, R. & Martínez Rincón, M. del C. (2014) Malnutrición asociada a disfagia orofaríngea en pacientes mayores de 65 años ingresados en una unidad médico-quirúrgica. Enfermería Clínica. 24(3), 183–190. DOI: 10.1016/j.enfcli.2013.12.009

[14] Sura, L., Madhavan, A., Carnaby, G. & Crary, M. A. (2012) Dysphagia in the elderly: management and nutritional considerations. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 7, 287–289. DOI: 10.2147/CIA.S23404

[15] Andrade, P. A., Santos, C. A. dos, Firmino, H. H. & Rosa, C. de O. B. (2018) The importance of dysphagia screening and nutritional assessment in hospitalized patients. Einstein (São Paulo). 16(2), 1–6. DOI: 10.1590/s1679-45082018ao4189

[16] Arrese, L. C., Carrau, R. & Plowman, E. K. (2016) Relationship Between the Eating Assessment Tool-10 and Objective Clinical Ratings of Swallowing Function in Individuals with Head and Neck Cancer. Dysphagia. 32(1), 83–89. DOI: 10.1007/s00455-016-9741-7

[17] Umay, E., Eyigor, S., Karahan, A. Y., Gezer, I. A., Kurkcu, A., Keskin, D., Karaca, G., Unlu, Z., Tıkız, C., Vural, M., Aydeniz, B., Alemdaroglu, E., Bilir, E. E., Yalıman, A., Sen, E. I., Alkatun, M. S., Altındag, O., Keles, B. Y., Bilgilisoy, M., Ozcete, Z. A., Demirhan, A., Gundogdu, I., Inanir, M. & Calik, Y. (2019) The GUSS test as a good indicator to evaluate dysphagia in

healthy older people: a multicenter reliability and validity study. European Geriatric Medicine. DOI: 10.1007/s41999-019-00249-2

[18] Rofes, L., Arreola, V. & Clavé, P. (2012) The Volume-Viscosity Swallow Test for Clinical Screening of Dysphagia and Aspiration. Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop Series. 72, 33–42. DOI: 10.1159/000339979

[19] Miller, J., Wells, L., Nwulu, U., Currow, D., Johnson, M. J. & Skipworth, R. J. E. (2018) Validated screening tools for the assessment of cachexia, sarcopenia, and malnutrition: a systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 108(6), 1196–1208. DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy244

[20] Reber, E., Gomes, F., Vasiloglou, M. F., Schuetz, P. & Stanga, Z. (2019) Nutritional Risk Screening and Assessment. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 8(7), 1065. DOI: 10.3390/jcm8071065

[21] Neelemat, F., Kruizenga, H. M., de Vet, H. C. W., Seidell, J. C., Butterman, M. & van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren, M. A. E. (2008) Screening malnutrition in hospital outpatients. Can the SNAQ malnutrition screening tool also be applied to this population? Clinical Nutrition. 27, 439–446. DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.02.002

Share this post:

Tag @flavourcreations with your shots and you could be featured on our page!

Customer Help

Inspiration

Connect

Other Flavour Websites

Stay Connected

Subscribe to receive recipe inspiration, blogs, new product launches, and more straight to your inbox.

Connect With Us

Customer Help

Online Store

Healthcare Food Service

Inspiration

Other Flavour Websites

Connect With Us