Free delivery on orders $350+

Free delivery on orders $350+

Connect With Us

One of the worst parts about ageing is not being able to do the things you could when you were younger.

Your muscles get weaker, so it’s harder to do things like exercise, play sport, and keep your house tidy. Most people accept this as inevitable. Getting older equals being more physically frail.

But what if that didn’t have to be the case? What if there was a simple way you could keep up your strength and minimise age-related muscle loss?

And there is: eat enough protein.

Seriously – not getting the right nutrients is one of the main causes of age-related frailty. That’s why we’re going to walk you through the importance of getting enough protein, as well as what you can do to improve your protein intake.

To understand why protein is essential for keeping up our strength and function as we age, we need to look at the role it plays in our bodies.

Protein is one of the three macronutrients (the other two are fats and carbohydrates).

Fats can be used by your body as a source of energy and help you absorb certain nutrients. Carbohydrates are your body’s main source of energy – they get broken down into glucose, which then gets converted into ATP (what your cells use to perform vital functions).

Protein, on the other hand, can be used for energy, but its main purpose is to build. Your body uses protein to grow and strengthen muscles, organs and cells.

Each protein is made up of many different amino acids, which are linked together in a long chain with peptide bonds. Sound a bit complex? It is, but stick with us – there’s a reason we’ve gone scientific on you.

Some amino acids can be produced naturally by our bodies (known as non-essential amino acids), but others can’t be. We can only get these essential amino acids through diet, which is one reason why getting enough protein in your food is critical.

With that in mind, here are some of the main functions performed by proteins.

Now we know what protein is used for by our bodies, let’s find out why it’s so important as we get older.

You probably already know that we naturally lose muscle mass and function as we get older – this process is known as ‘sarcopenia’. The average healthy person loses 3–8% of their muscle mass per decade, starting from 40–50 years of age [1].

Although sarcopenia might not seem like a big problem, the long-term effects can seriously impact your quality of life. Two of the most common issues associated with sarcopenia are impaired daily function and an increased risk of falls [1].

Together, these two issues can quickly strip us of our ability to do the things we love – and, when combined with illnesses, injuries, and malnutrition, can compromise our health and make independent living difficult.

The right nutritional intake – combined with an active lifestyle – can slow the onset and effects of sarcopenia, making a healthy ageing process achievable. Having the right balance of protein, carbs and fats means that your body has the energy to function properly (without breaking down proteins for energy) and has the protein necessary to maintain existing muscle mass.

Heard of peptides? What about keratin, or elastin?

You can find all three listed on beauty and skincare products – but they’re not some synthetic chemical or secret serum.

In fact, peptides, keratin and elastin are all amino acids (the structural units that make up proteins), and, along with various vitamins and minerals, they’re necessary for healthy skin. They work together to produce and support collagen, which is a type of protein that keeps your skin looking healthy.

Unfortunately, our natural collagen production slows down significantly as we get older, which, combined with environmental stressors like sun, pollution and oxidisation, causes our skin to get wrinkly [2]. Some of these stressors can even lead to chronic diseases like cancer [3].

Getting enough amino acids from protein in food is essential for creating collagen. Science shows that, when the right amino acids are consumed, the effects on your skin can be excellent. One study found that consuming collagen peptides (in conjunction with vitamin C, zinc, biotin, and vitamin E) significantly improved skin hydration, elasticity, roughness and density for all participants [4].

Some amino acids can also have other beneficial effects on your skin. Peptides derived from food proteins, for example, have been found to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties [5].

To slow down the ageing process that affects your skin, you need to make sure you’re getting enough protein in your diet.

If you’ve read this far, you’re probably thinking, “Well, getting more protein sounds simple enough. When do I start?”

Unfortunately, it’s not that easy. There are three big challenges to getting enough protein as an older adult:

Let’s take a look at what each of those means.

Decreased food intake for older adults occurs because, as we age, we tend to eat less food. This occurs for two reasons. The first is that being older generally means our bodies process food more slowly, leaving us feeling fuller for longer [6]. Secondly, our hormones also change – the satiety hormone cholecystokinin is more concentrated, and ghrelin, the hunger hormone, is less easily activated [6].

So, as we age, we’re less hungry (which normally means we eat less) – but what happens to the food that we do eat?

Unfortunately, our bodies become less effective as we age, and that translates to how we absorb nutrients through the gut. Some amino acids, like leucine, aren’t absorbed as well, while others are just absorbed more slowly [7, 8].

Finally, our bodies also need more nutrients as we age. Because we’re often less active, most people need a lower-energy, nutrient-dense diet [6]. High protein is especially important for maintaining muscle mass, and chronic conditions can also increase protein expenditure [6]. Another consideration is anabolic resistance, which occurs when older adults develop a resistance to synthesising proteins from dietary protein, making the protein they do eat less effective [6].

So exactly how much protein should someone over 65 be eating?

Many studies have concluded that older adults need at least 1.2–2.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day [7, 9, 10].

The average weights for Australian males and females over 65 are 83 kilograms and 71 kilograms respectively, which would mean recommended protein intakes of 99–166 grams and 85.2–142 grams.

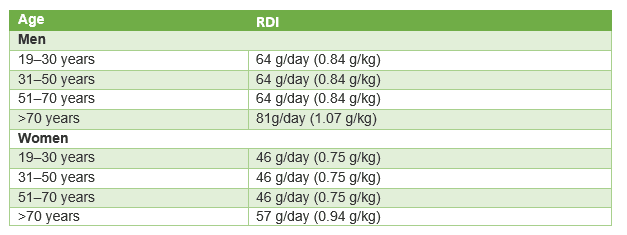

This is well above the recommended dietary intakes (RDIs) for older people, which indicate the minimum daily protein intakes.

Ultimately, everyone’s body and nutritional requirements are different. When possible, consult a dietitian to figure out how much protein you should be eating each day.

There are lots of different foods older people can eat to get the protein they need. The key is to pick protein-dense foods – this means you’ll consume a lot more protein before you start feeling full.

Here’s a list of some great protein-rich foods you can incorporate into your diet:

To help your body process protein as effectively as possible, it’s a good idea to get your daily protein intake across every meal, rather than having most of it towards dinner (which is what many Australians do).

One nutritional summit concluded [1]:

Habitually consuming 25–30 g protein at breakfast, lunch, and dinner provides sufficient protein to effectively and efficiently stimulate muscle protein anabolism and may delay the onset of sarcopenia, slow its progression, and/or reduce the magnitude of its functional consequences.

This is often easier said than done. If you prefer a light breakfast, or if you don’t feel like eating meat or fish with every meal, it can be hard to distribute your protein intake across every meal.

The solution? Food fortification powders like AdVital Powder. Each scoop of AdVital Powder comes loaded with 15 grams of protein and 27 vitamins and minerals, and mixes taste- and colour-free into your favourite foods and drinks.

Like toast and jam in the morning? Have AdVital-enriched jam on protein-dense Ezekiel bread. Prefer a bowl of milk and cereal? Mix a scoop of AdVital Powder into your milk, and enjoy it with oats.

You can even mix AdVital Powder into drinks like orange juice and coffee, making it simple to boost your protein intake at any point during the day.

One of the easiest ways to slow the ageing process is to eat the right nutrients. Protein is essential for maintaining and repairing tissue, and getting enough of it can lead to better strength, more independence, and a higher quality of life.

To make sure you’re getting enough protein, try to eat a reasonable amount of protein with every meal, and remember to combine that intake with a balanced diet, regular exercise, and plenty of water.

Want to learn more about the relationship between diet and healthy ageing? Hit the button below to find out the nutritional secrets to ageing healthily.

Medical information on AdVital.com.au is for general information purposes only and is not the advice of a medical practitioner. Information on AdVital.com.au was accurate at the time of publication. For more information about nutrition and your individual needs, see your GP or an Accredited Practising Dietitian.

[1] Paddon-Jones, D., Campbell, W. W., Jacques, P. F., Kritchevsky, S. B., Moore, L. L., Rodriguez, N. R., & van Loon, L. J. C. (2015). Protein and healthy aging. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 101(6), 1339S–1345S. DOI: 10.3945/ajcn.114.084061

[2] Varani, J., Dame, M. K., Rittie, L., Fligiel, S. E. G., Kang, S., Fisher, G. J., & Voorhees, J. J. (2006). Decreased Collagen Production in Chronologically Aged Skin: Roles of Age-Dependent Alteration in Fibroblast Function and Defective Mechanical Stimulation. The American Journal of Pathology, 168(6), 1861–1868. DOI: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051302

[3] Kruk, J., & Duchnik, E. (2014). Oxidative stress and skin diseases: possible role of physical activity. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 15(2), 561–568. DOI: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.2.561

[4] Bolke, L., Schlippe, G., Gerß, J., & Voss, W. (2019) A Collagen Supplement Improves Skin Hydration, Elasticity, Roughness, and Density: Results of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Blind Study. Nutrients, 11(10), 2494. DOI: 10.3390/nu11102494

[5] Chakrabarti, S., Jahandideh, F., & Wu, J. (2014) Food-Derived Bioactive Peptides on Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Biomed Research International. DOI: 10.1155/2014/608979

[6] Clegg, M. E., & Williams, E. A. (2018). Optimizing nutrition in older people. Maturitas, 112, 34–38. DOI: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.04.001

[7] Baum, J. I., Kim, I.-Y., & Wolfe, R. R. (2016) Protein Consumption and the Elderly: What Is the Optimal Level of Intake? Nutrients, 8(6), 359. DOI: 10.3390/nu8060359

[8] Milan, A. M., D’Souza, R. F. D., Pundir, S., Pileggi, C. A., Barnett, M. P. G., Markworth, J. F., Cameron-Smith, D., & Mitchell, C. (2015) Older adults have delayed amino acid absorption after a high protein mixed breakfast meal. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 19, 839–845. DOI: 10.1007/s12603-015-0500-5

[9] Donaldson, A. I. C., Johnstone, A. M., de Roos, B., & Myint, P. K. (2018). Role of proteins in healthy ageing. European Journal of Integrative Medicine. DOI: 10.1016/j.eujim.2018.09.002

[10] Sieber, C. C. (2019). Malnutrition and sarcopenia. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. DOI: 10.1007/s40520-019-01170-1

Share this post:

Tag @flavourcreations with your shots and you could be featured on our page!

Customer Help

Inspiration

Connect

Other Flavour Websites

Stay Connected

Subscribe to receive recipe inspiration, blogs, new product launches, and more straight to your inbox.

Connect With Us

Customer Help

Online Store

Healthcare Food Service

Inspiration

Other Flavour Websites

Connect With Us